You Do Not Speak For The Bees.

Apiculture and anti-natalism

Known effective altruism troublemaker Matthew Adelstein, more commonly known as Bentham's Bulldog, recently caused quite the commotion with his essay on the ethics of eating honey. In said essay, he argued (emphasis mine):

If you eat honey, you are causing staggeringly large amounts of very intense suffering. Eating honey is many times worse than eating other animal products, which are themselves bad enough

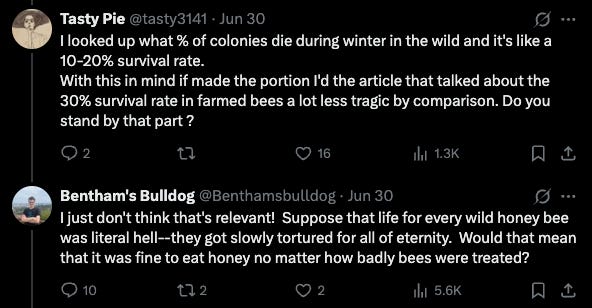

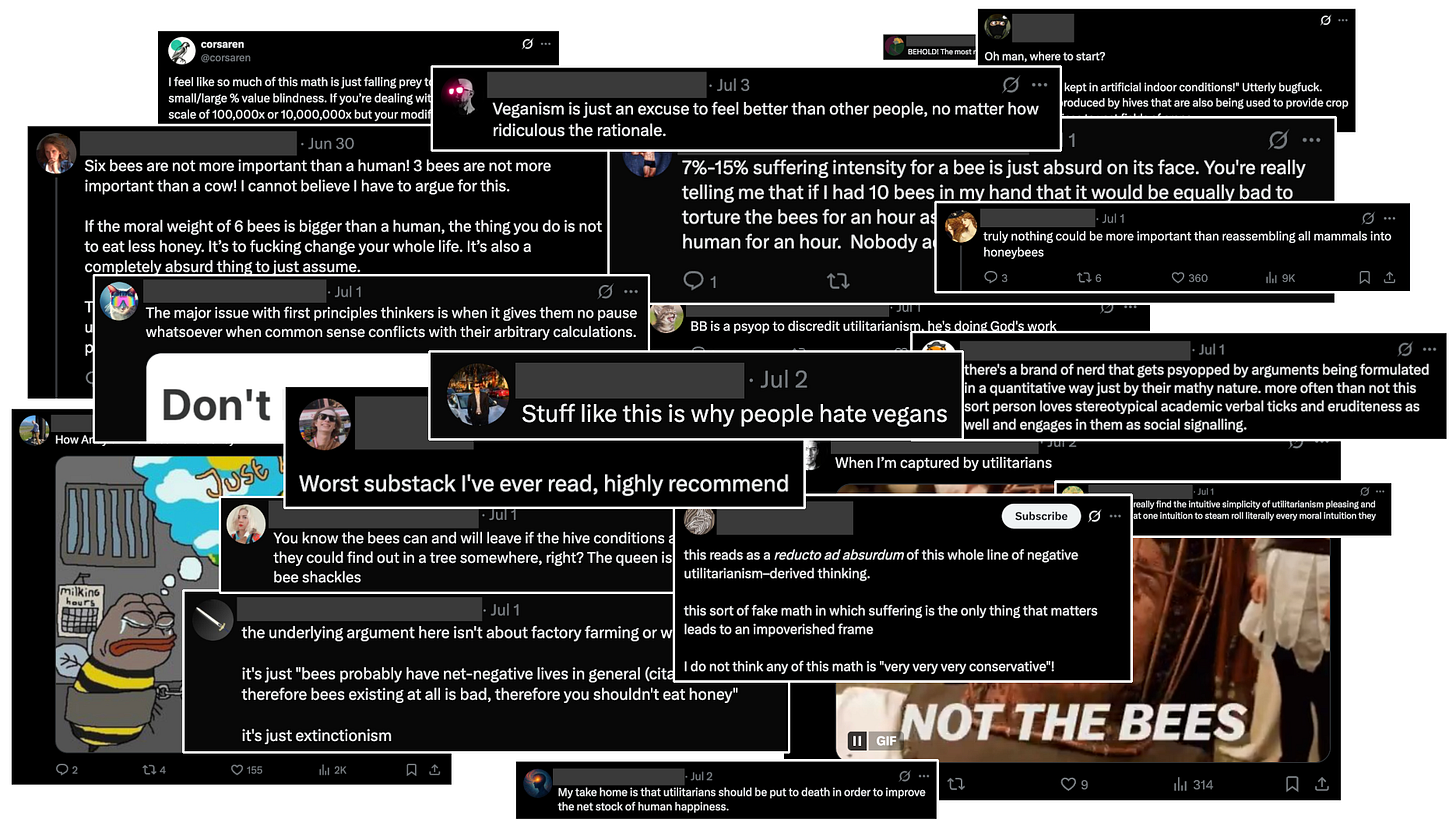

Naturally, this made a lot of people very angry.

I.

Arguments for veganism—particularly moral ones—tend to produce rather intense reactions. The writer is, after all, accusing animal product consumers of participating in an act of extreme evil. The average U.S. resident consumes over 1.3 lbs. of honey per year. If Adelstein’s claims are correct, then you and I are likely responsible for causing untold suffering upon the lives of millions (of bees).

Nobody likes to be told they are a bad person; they certainly don’t like being told this by a smarmy college student with questionable metaethics.

But here’s the thing: I like Adelstein—I am a paid subscriber to his blog. Sure, he sometimes has takes that I find totally absurd and unpalatable, but that’s part of the fun. After all, I myself was once a smarmy college student with questionable metaethics, so I really am in no position to be casting stones.

So let us leave personal indignation at the door for a moment and engage with the object-level discussion. If somehow you have not read the original piece or Adelstein’s follow-up post, I would encourage you to do so, but the rough argument is this:

Bees in the honey industry suffer tremendously: they are subject to stressful living conditions, have short lives, and experience painful deaths; Adelstein estimates that a farmed honey bee’s life is ~10% as unpleasant as that of a factory chicken (which is very bad)

Many more bees are required to create honey than are required to make other animal products: 200,000 days of bee farming per kg of honey vs. 23 days of chicken farming per kg of poultry

Bee suffering is a genuine moral concern: Despite their size, bees are estimated to experience suffering ~15% as intensely as humans (vs. 33% for chickens)1

Therefore, eating honey causes many times more suffering than other types of animal products and ought to be avoided

Now, there are many objections that one might make here,2 to the point that it might be easy to dismiss all of this discourse as a dumb sideshow.

You expect me to listen to an argument about bee suffering? Really??

Yet despite the cheeky comment I made in my last essay, I’m not going to argue for the complete moral irrelevance of bees. Nor am I going to pick a fight with Adelstein’s conclusion against eating honey per se. I may not be a vegan myself, but I’m generally supportive of those who are.3 I think they genuinely want to do what is best—which is more than can be said for many—and I’m open to the idea that they may even be right. If eating honey were the only thing at stake here, I wouldn’t be wasting so much digital ink.

No, the reason I feel compelled to write this essay is that I believe there is something deeply rotten at the core of this protreptic.4 A malignant tumor shifting underneath the surface that must be excised, no matter the author’s altruistic intent.

You see, a cursory reading of the no-honey argument would suggest that it is primarily about the immorality of human treatment of bees. That by using unethical farming practices, beekeepers cause their hives to suffer excessively and unnaturally. And so by consuming honey, we normal folk encourage said practices and cause more bees to suffer under those conditions. Ipso facto, eating honey is wrong.5

This is, after all, how most people talk about factory farming. It’s not the farming that is wrong; it’s the factory.

However, this reading would be incorrect—or at the very least incomplete.

For although Adelstein does believe that the beekeeping industry is brutal, this belief is not actually all that load-bearing. As he was clear to point out in follow-on discussions: even if the lives of farmed bees were much better than those of wild bees, that fact would not absolve the practice of bee farming.

How? How could giving bees a better life than what they would have in the nature constitute a morally wrong act?

Simple. Because if the honey industry didn’t exist, then those bees would never have been brought into this world in the first place. And to Adelstein, to give life to a bee is to condemn it. He thinks the average bee would be better off if it simply never existed.

Adelstein is, in other words, a honey bee anti-natalist.

To those not versed in things like negative utilitarianism,6 I expect that this sort of anti-natalist position may appear uniquely bizarre, if not downright unsettling.

After all, if creating 10,000 bee lives is bad, does that mean preventing 10,000 bee lives is good? Wouldn’t this imply that we should take actions which reduce bee populations, such as sterilization and ecosystem destruction? Even worse, wouldn’t this mean that full-blown extinction is actually an ethically desirable outcome?

Well, it turns out that Adelstein has written about insect welfare quite a lot and his answers to these questions are quite clear: yes, yes, and yes.

Or, to boil it down to a single quote:

I think that killing insects is probably good because [they live] bad lives.7

Perhaps now you understand my true motive for writing this essay.

II.

Animal anti-natalism is nothing new—it is a view most famously advocated by Brian Tomasik, a thinker whom Adelstein cites frequently. Nor am I the first person to express outrage at these sorts of arguments. I think an instinct to ridicule is a natural reaction to statements such as these (emphasis mine):

The good news is that mass extinctions have effects that last millions of years and that these lower productivity and diversity8

But while I thoroughly believe that you ought to regard such positions with skepticism, suspicion, and even outright contempt,9 I do think that many of the objections to anti-natalism are poorly made. These critics confuse the impossible with the unjustifiable and mistake dangerous arrogance for mere absurdity.

This essay seeks to remedy that.

But in order to understand the true error at the core of anti-natalism, we must first examine why the most common objections fail.

You see, the first and most natural temptation when faced with an appalling worldview such as anti-natalism is to treat it as a reductio ad absurdum—to argue that because we have reached an insane conclusion, one of the premises must therefore be necessarily false.

This seems fair: it does appear prima facie absurd to argue in favor of species-wide genocide on behalf of the species in question—surely there is no possible universe where exterminating a living organism could be to its benefit! Surely an act so horrible and extreme could never be the solution! Surely it must always and forever be the most evil of sins!

Right?

Well, not so fast. Let us steelman the anti-natalism argument a little bit here, shall we? Note that since I don’t care about the ethics of honey specifically, the argument that I’m going to reconstruct will be a little different than the one I summarized above.10

The first major premise of Adelstein’s broader anti-natalism argument is simple: bees and other insects live terrible lives. He paints the picture of stressed, exhausted creatures, working under dangerous and vile conditions, subject to all manner of pain, suffering, and death, with little in the way of compensating pleasure. A life so destitute that it would be better off not to exist.

Moreover, he imagines that this poor, miserable life is not merely an outlier, but the norm11 across millions of hives and trillions of bees. From the coasts of California to the valleys of the Italian Alps, there are but two certainties in a bee’s life: honey and suffering.

If you want to understand how a person could possibly justify something as drastic as involuntary mass extinction, just imagine what this actually means. Imagine a life of true wretchedness, one so painful and hopeless that if offered the choice between that life and oblivion, you would voluntarily choose the latter. Then imagine that life repeated at an unimaginable scale.

There are three trillion bees globally, roughly 30 times more than the total number of humans who have ever existed. In addition, there are estimated to be another 10^18 total insects worldwide, which Adelstein asserts to be suffering a similar fate.

And so if the anti-natalists are right—if insect lives truly are horrible—then the scale of this collective suffering is unimaginable. It means that hell on earth is not limited to the war zones of Sudan or Ukraine—it is happening right now, in your backyard. If insects could scream, their agony would drown out the world.

We’ll revisit whether this bleak view of the world is correct or not. But for now, just imagine that this truly is the natural state of things. Does such an extreme situation not call for extreme action? How could it not?

This is where Adelstein’s second major premise comes in: we ought to take actions which reduce the amount of suffering lives, up to and including the prevention of those lives from ever existing.12 In essence: if one life is negative in expectation, then it is good to prevent it; if an entire species’ lives are negative in expectation, then it is good to exterminate it.

Now let’s ask the key question: is any of this impossible? Are either of these premises necessarily false?

Despite my strong objections to anti-natalism, I’m not so sure.

Imagine, for example, a species that truly does suffer horribly from the moment it is conscious to the moment that it dies. No matter where it is or what it does, this creature experiences pain as if it were being repeatedly stabbed in the stomach—a full life whose very moment-to-moment existence is nothing but torture. Let’s call this creature a Miserodon.

Is it possible that the Miserodon is better off extinct?

I think the answer here is obviously yes. After all, no matter how much we value life, there must be some amount of suffering which is so great that non-existence is preferable. To deny this claim would be to deny that suicide can ever be rational. To deny this claim would be to argue that even the biblical Hell must be a gift.

Note that this mere possibility alone already justifies Adelstein’s second premise—if it is possible to promote extinction, even if this requires extreme circumstances, then premise two cannot be necessarily false. But what of premise one? Is it even possible that insects are actually suffering this much?

After all, you may object: if the Miserodon’s suffering is so vast, wouldn’t a creature such as the Miserodon simply kill itself? Wouldn’t it choose to end its own suffering? And doesn’t the fact that bees (and wild animals generally) seem to never engage in suicide suggest that they are not, in fact, like the Miserodon?

Well, here Adelstein has two more responses:

First, we can imagine that the Miserodon, despite suffering immensely, is simply incapable of killing itself. Perhaps the thought never occurs to it because it lacks the ability to cognize such an option—it doesn’t know what death is and doesn’t realize that it has the option of dying. Perhaps it has no ability to kill itself given the contents of its surroundings. Perhaps it still feels the urge to do tasks which keep it alive, such as eating or sheltering, even though it would prefer not to be alive at all. In this case, the lack of suicide would not indicate a lack of desire to end one’s life, and it would certainly not constitute a judgement that its life is worth continuing.

Second, we can also imagine that the Miserodon is not suffering every waking moment. Instead, we can imagine that it lives for two days, but then dies a horrible, horrible death, full of the most excruciating pain that one can imagine. So, even though during those two days the Miserodon may not experience a life that is inherently net-negative, when it’s all said and done and the body is cold, the total life of the Miserodon is still not worth living.

What would it even mean to say that a life wasn’t worth living until it was over? Well, let us imagine that you could talk to the Miserodon in the afterlife, immediately following its horrible demise. You ask it a simple question: knowing how your life just went, including how you died, and knowing that this is typical for members of your species, do you want to reincarnate as a Miserodon once more?

We can then assume that the death of the typical Miserodon is so painful, and their remaining life so short and mediocre, that every single member of this species would say no. They would all choose oblivion over existence, despite having not made that choice during their own lives.

I don’t think either of these scenarios are all that implausible. Evolution does not select for lives which are happy per se; it selects for lives which are good at reproducing. A miserable yet efficient replicator is still a good replicator. And if we imagine that we are living in the Least Convenient Possible World, it certainly seems that the existence of the Miserodon is not fully precluded.

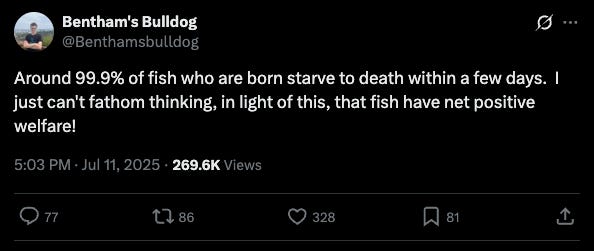

In fact, Adelstein argues that the life of most fish largely resembles the second option, with a very brief life followed by painful death:

Remember, we’re asking if the animal’s life is positive in expectation, i.e., if the probability-weighted life of this creature is worth living taken as an average across all of its kin. The fact that some species are r-strategists does mean that most of their lives could plausibly be horrible. And so if we also then assume that the lives of the few who do survive are not so incredibly net positive as to outweigh this,13 then the expected value of each new life could be negative as well.

But hold up! Now look where we are. What started as an attempt to show that anti-natalism is absurd has seemingly shown that both of the key premises underlying it are, at least in some universe, quite reasonable.

That’s the thing about anti-natalism. If it were just a silly internet argument that was easy to disprove, that would be one thing. We could dismiss it offhand and pay it no further mind. But that is simply not the case.

Brian Tomasik is a well-known name in the effective altruism and animal-ethics spheres. Adelstein himself is probably one of the more well-known EA bloggers, and he regularly advocates for arthropod population reduction not merely as a small ethical fancy, but as the single greatest ethical issue of our time.

This is not a niche cause.

Anti-natalism is not dangerous because it is absurd; it is dangerous because it isn’t.

III.

I think where a lot of commentators go wrong on this issue is that they attempt to argue against anti-natalism and species genocide as a theoretical matter—that, as a matter of principle, causing the extinction of a species is always, universally bad. In essence, this constitutes a claim that it is impossible for there to exist a world where driving a species into extinction is a morally desirable outcome.

But this is, of course, false. We already inhabit such a world. In another essay, Adelstein points to the new world screwworm, a species whose reproductive cycle relies on laying its eggs in the flesh of other animals so that their maggots can eat their way out. This no doubt causes immense suffering and I’d be perfectly willing to consider an argument for said species’ extinction, just as I would for mosquitos that transmit malaria or yellow fever.

The difference between the screwworm and the bees example is, of course, that screwworms cause harm to others, and so extinction is a punishment rather than a supposed blessing. But from a theoretical standpoint, that hardly seems to matter much. As we saw with the Miserodon, you can easily imagine a species which, when born, causes the exact same amount of suffering as the screwworm but simply to itself or its kin, and the calculus barely changes.

But while anti-natalism doesn’t fail on theoretical grounds, we can show that it fails as a practical matter: that as limited beings in this universe, we are not justified in concluding and acting upon the belief that large swaths of animal species are better off extinct.

The benefit of switching to this practical lens is twofold:

It modifies the question from a theoretical concern about what is welfare maximizing to a practical concern of whether we are justified in taking specific action (e.g., sterilization, genocide, etc.)

It shifts the burden of proof onto the anti-natalist, for reasons we shall see shortly

So with that in mind, let’s revisit those key premises:

P1: Are Bee Lives Terrible?

Earlier we established that, conditional on bee lives consisting of net suffering, their cumulative suffering and the moral worth of said suffering is almost certainly vast. We also established that this scenario isn’t a priori impossible. But is this actually the case? Are bee lives actually net negative?

Adelstein’s argument here is not terribly comprehensive—it’s honestly rather flimsy. But it essentially boils down to three claims:

A bee’s life contains a lot of negative experiences

A bee’s death is typically very painful

A bee’s life does not contain enough positives to outweigh the above two facts

Let’s look at the evidence.

P1.1: A bee’s life contains a lot of negative experiences

First, do the day-to-day lives of honey bees, excluding their manner of death, include a lot of negative experience? Here’s what Adelstein has to say about farmed honey bee conditions (emphasis mine):

They’re mostly kept in artificial, conditions, in mechanical structures that are routinely inspected in ways that are very stressful for the bees, who feel like the hive is under attack…

In order to prevent this, the industry uses a process called smoking…Sometimes, however, smoking melts the wings of the bees (though my sense is this is somewhat rare)…

The industry also keeps the bees crammed together, leading to infestations of harmful parasites…

Bees also undergo unpleasant transport conditions…The transport process is very stressful for bees, just as it is for other animals…

They’re overworked and left chronically malnourished…

Ehhhhhhhh?

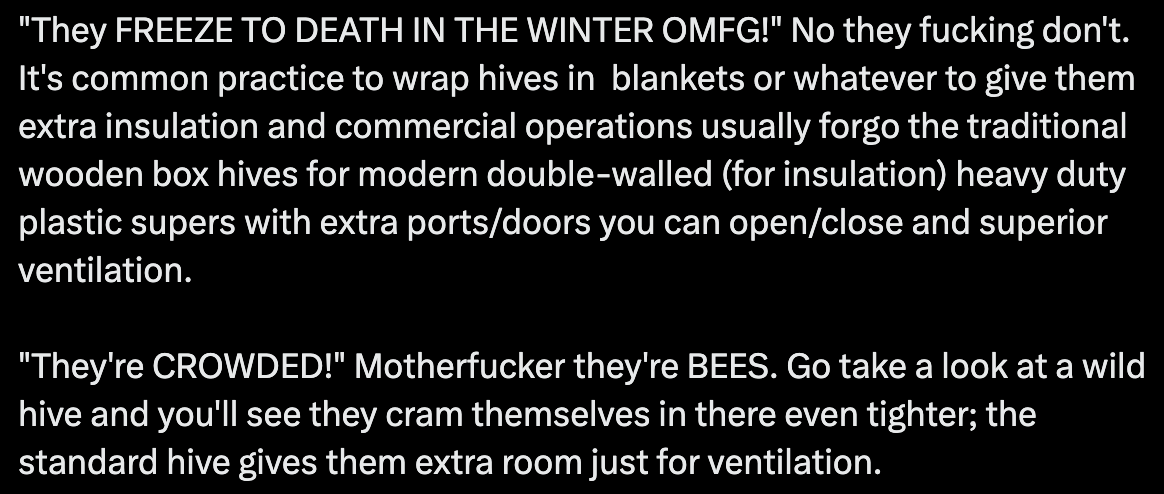

Stressful inspections? Cramped beehives? Rare instances of mishandled smokers melting wings?

Look, I don’t want to sit here and nitpick the details,14 but none of this strikes me as obviously horrific. Perhaps some are a bit unpleasant, but it all seems pretty low stakes—at least in the context of anti-natalism. The malnourishment that Adelstein cites is related to micronutrients, not famine. The unpleasant transport conditions only seem to occur, at most, 3 times a year to 2/3rds of bee colonies, which due to the average lifespan of a bee means that only 13% of US bees experience this annually.15 And the “artificial mechanical structures” look like this:

Not to be dismissive, but I don’t think the bees are experiencing much psychological distress at the apiary equivalent of Ikea furniture.

In fact, many beekeepers were quick to point out that some of the conditions which Adelstein describes, such as low thermal insulation or crowded quarters, are perfectly normal, if not worse, for bees in the wild.

Granted, Adelstein would surely argue that those wild bees are also living through hell, but frankly, I’m not convinced. If bees have evolved to densely occupy their nests then why would we assume they find such conditions unpleasant? Why wouldn’t they simply enjoy the close company of their kin?

As for parasites, I won’t pretend that mite infections are good or comfortable experiences, but I’m skeptical that they amount to truly ghastly conditions in expectation. Only a fraction of bees suffer from them, and the report which Adelstein cites points out that beekeepers are the ones actively trying to prevent these parasitic outbreaks. If anything, this is a point in favor of beekeeping as a welfare improving activity.

All in all, none of this is sufficient to convince me that the average day in the life of a bee is some unspeakable horror. I certainly could not, on the basis of these experiences alone, justify the extinction of an entire species!

Yet perhaps Adelstein’s single strangest assertion is that bees are “overworked”, as if they are slogging through their honey-making labor like a bad 9-to-5.

I’m sorry, but this is just an incredibly pessimistic way to view the world. Making honey is what bees live for! It is their purpose, their calling, their apis raison d'être! The notion that they could only experience this work as a net negative requires an absolutely bizarre account what living is like. It is the sort of position that one could only reach if one were actively looking for reasons to think that bees are suffering…

…it is the sort of position that one could only reach if one were actively looking to justify a mercy killing.

For the rest of us, the notion of gaining satisfaction and utility from one’s work is obvious. Ask a carpenter how it feels to see a shelf completed. Ask a painter how it feels to stand before a finished piece. Ask a mother how it feels to see her child eat.

Look, all I’m saying here is that if my questionably autistic uncle can derive what seems to be immense pleasure from building model trains, then surely we can hypothesize that bees might derive similar pleasure from building their hives. One must imagine the manic pattern builder happy.

In a livestream discussion on The Bees with fellow blogger TracingWoodgrains, Adelstein made a comparison to gambling addicts. He argued that gambling addicts demonstrate a case where agents can have preferences and desires without experiencing actual hedonic pleasure from satisfying those desires.16 Moreover, we as outsiders can judge that the act of fulfilling said desires is actually harmful for the gambling addict, no matter how unwilling they are to stop.

Similarly, I imagine Adelstein might argue here that just because bees seem to want to build their beehives, it does not mean they actually derive pleasure from that experience.

But notice: I am not asserting that bees necessarily love building their hives or collecting flower nectar, merely that such a scenario is highly plausible. This is what I meant by the shift in burden that results from this practical lens. Whereas before the anti-natalist was able to defend the mere plausibility of hell on earth, now it is incumbent upon him to demonstrate its reality. This means it is not enough to show that bees could be like gambling addicts; we’d actually need positive evidence that they do not derive pleasure from the very activity they dedicate their lives to.

I consider this burden shift to be wholly appropriate—if you are going to advocate for the extinction of a species, the destruction of a habitat, or even just the mass prevention of new life, it is on you to justify that action, and the bar for certainty ought to be, frankly, astronomical. You are asserting a great deal of authority and power over creatures that are helpless to stop you. Their lives hang in the balance. You cannot unring that bell!

Given all of the above, I’d say that the negative day-to-day experiences of honey bees are largely insufficient to justify the hell-on-earth scenario we had before. In fact, I’d be willing to guess that the typical day of a honey bee is net positive, all things considered. Certainly if I was given the options of living as a bee under those conditions vs. never existing, I’d happily pick the life of a bee.

Okay, but that’s just living as a bee, what about dying as one?

P1.2: A bee’s death is typically very painful

You see, the pain of dying is actually the core thrust of Adelstein’s argument. Consider this quote from his essay Against Nature (emphasis mine):

Most insects have short and terrible lives. Reducing the number of insects that are born into a brief and hellish nightmare of an existence before being painfully killed is a very good thing…

…is living for a week and then being eaten alive or starving to death a life worth living? Obviously not. If a human baby lived for about a week and then was eaten alive, no one would think their happiness during the week could offset the harm of being eaten alive. This is especially so if that week of existence was filled with hunger, thirst, and fleeing from predators. I don’t know exactly how many months or years of happy life I’d have to be guaranteed to be willing to endure the experience of being eaten alive, but it’s sure as hell more than a week.

If you ignore the sensationalist bit about human babies, here we start to see a more reasonable argument for the dreadful life of bees. The main argument is that, because bees and insects have very short lives, and their deaths are quite painful, then that means they don’t have much time to “offset” the pain of dying. In a sense, every bee is born into this world in utility debt owing to the suffering entailed by its inevitable demise. A depressing proposition indeed, but let’s examine it.

In the honey article, Adelstein lists off various causes of death for bees including:

Freezing during the winter

Overheating

Predation

Parasites

Pesticide poisoning

Being crushed to death after hive inspections

Stinging

Starvation

Some other causes of death include:

Wing-failure / wear-and-tear (allegedly this is the most common cause of death for workers)

Mating (drones only)

Now, many of these do sound quite painful. But I’m also not convinced that all of these are unspeakable horrors either. Being crushed to death could be very quick. Freezing to death is an inherently numbing experience even if it is still painful. Dying in the defense of your hive could easily be as glorifying as it is painful. Hell, death by orgasm is probably a net positive experience, even if it involves your abdomen ripping apart.17

My point here is not that these forms of death do not entail great suffering—my point is that it does not seem inconceivable to me that a life punctuated with one of these experiences could still be worth living, particularly when you consider that not all bees die this way.

Which brings us to the last premise:

P1.3: A bee’s life does not contain enough positives to outweigh the above two facts

As we’ve already established above, I think the day-to-day work of a bee may be quite a pleasant experience. I certainly don’t have overwhelming reasons to believe otherwise. Let’s also not forget that bees can fly, which on its own sounds pretty sweet.

Yet Adelstein’s crux is that he thinks any positives which do exist in a bee’s life cannot possibly outweigh the negatives above—particularly the pain of death. Most of his argument here simply stems from the lifespan of the bee, and the limited time they have to capture positive utility.

I do grant that the short lives of bees pose an issue, though it is worth qualifying that we cannot be sure if bees experience time the same way as us. They are small creatures with very different brains—a human baby can’t do much in three weeks, but who’s to say that this same time period for a bee is insufficient for a full and happy life?

As such, the only real question we need to ask is what sort of positive value could a bee accrue during this time, and could that ever outweigh being squished?

Here, Adelstein once again downplays the benefits available to bees. In that same livestream discussion with Trace, he argued that bees are limited to purely hedonic pleasures—unlike humans, they cannot experience higher virtues from art or love or learning. And sure, I’ll grant that these more intellectual pleasures are inaccessible to our fuzzy friends. Yet I still find this argument to be incredibly peculiar.

After all, Adelstein clearly believes that honey bees are capable of experiencing suffering in much the same way that human beings do (adjusted for their level of consciousness). He thinks that a bee getting squished is just like a human getting squished, only ~15% as intense.18 In general, he does not seem to think that the worst forms of suffering are unique to humans, yet he does think that this is true for pleasure. In a sense, he imagines that bees experience only a narrow slice of the possible valence spectrum, where that slice includes all of the worst possible valences but none of the most positive ones.19

I’m not going to get into the metaphysics of consciousness here to rigorously test the plausibility of this theory, but it does strike me as odd to imagine that evolution would not make full use of the potential degrees of positive and negative that are available. It is odder still to judge the valence spectrum of a bee on the basis of our own. I will have more to say on this another time.

For now, even if we do adopt this asymmetry of valence and hold that bees are capable of great suffering but not great pleasure, I still believe that Adelstein’s argument misses the mark. Because what is common to all of these anti-natalist screeds is that they tend to heavily discount—if not outright ignore—the simple value of being alive.

I take this value to be self-evident and fundamental.

It is the rhapsody of being that permeates every moment and the miracle of consciousness that we lucky few must cherish. It is the source of that stubborn and universal will to live which resides inside every creature on this earth and it is the innate vitality that keeps us striving even in our most desperate moments. It is the wave of regret that hits right as you jump from the bridge.

It is joie de vivre in its purest sense.

It is the reason I am so terrified of death.

If you don’t know what I’m talking about, then please, go outside right now and breath some fresh air. Experience the ecstasy of existence and the bounty of being. Squish your feet into the marshy soil of the stream and run your hands along the skin of a sycamore tree. Go feel the sensation of the world at your fingertips and thank God you get to experience the miracle that is life for at least one more day.

Sure, all of the above acts are largely pleasurable, but I don’t think the pleasure alone is all of what makes these experiences magical. Some of us may grow so accustomed to these omnipresent slivers of grace that we become numb to them. But if you are willing to step back and examine them with a true child-like curiosity and wonder, you should see that it is quite literally the qualia of experience and consciousness itself that is inherently sublime.

What I’m saying is that even in the absence of some grander teleology, the meaning of life is life itself, and it has a majesty all its own—a merit not merely reducible to pleasure or comfort or the absence of pain, but an intrinsic value that comes from the wondrous effervescence of existence.

And this underlying value of living means that, even if an activity comes with overall negative valence experiences—experiences that I would disprefer over literally doing nothing—I’d still choose them over not existing.20 I would take a sweaty day in an Atlanta heatwave or an evening eating chicken wings covered in Da Bomb hot sauce over a day not lived. I do not want to turn off my brain and hide from the pain.21 I do not want to shelter myself from experience. I want to be alive and all that that entails.

Yes, I am essentially telling anti-natalists to touch grass. But it’s true!

The very moment-to-moment experience of being alive is filled with so many tiny miracles, so many cherished sensations and qualia that anyone who is skeptical of the desire to live is either being pedantic or clinically depressed. I realize that negative utilitarians are probably tired of hearing this objection—but I am deeply sorry to inform you that it is common for a reason!

If I am being frank, I think the claim that wild animals are better off unborn is a rather embarrassing admission—you are, in a sense, telling on yourself. You’re saying that if deprived of all your modern conveniences—your apartment, your dishwasher, your Lululemon pants—and forced instead to fend for yourself in the wild, you would be despondent. You would give up. You would sooner be euthanized.

This is abnormal! Most humans will go to great lengths to stay alive. ~10% of US healthcare spending comes in the last 12 months of life. That’s ~$430B spent on what accounts for 1.25% of our time on this earth—a figure that doesn’t even account for the generally poor quality of that time. Patients will regularly buy hundred-thousand-dollar lottery tickets for a chance at another year. And sure, much of that money probably isn’t worth it—it could be better used elsewhere for even more life-fulfilling activities. But the fact that we spend it anyways shows just how much we value life itself even if the quality of that life is poor.

Adelstein asks if any of us would choose to live for an additional three weeks of mediocrity if we knew that said period might end in a pain and suffering—and the answer empirically seems to be yes! I would imagine that many bees might feel similarly!

I realize that many of my arguments here haven’t been terribly philosophical or rigorous. You could reasonably chalk much of this up to vibes and aesthetics. That is because this is a topic that mostly consists of debating alien hypotheticals. We must reason about a creature whose experiences we have never shared, making a choice that it has never been offered, by weighing preferences that almost nobody agrees on. If you think being “transported in a stressful manner” is bad enough to commit suicide,22 then honestly, I don’t know what to say to you besides: “You are a massive pansy, please do not make decisions about other beings’ lives if you value yours so little!”

And it is that last claim there—that you have the right to make decisions about the lives of others—that I feel I must repudiate most viciously. Just because you would prefer oblivion over being, doesn’t mean you get to decide for anyone else.

So let us turn to that second major premise.

P2: Should we prevent lives from existing if we expect them to be net negative?

Remember our thought experiment with the Miserodon—the creature that lives the terrible, unbearable life? Remember how we ultimately stipulated that, when given the choice to be reincarnated, every single member of its species opts instead to embrace the void?

Well, you see, that stipulation was load-bearing.

Because imagine if that wasn’t the case. Imagine if, despite its endless suffering, this poor little creature kept coming back for more. Imagine if every time it arrived at the threshold of the beyond, it chose again and again to be reborn, knowing full-well what lay in store.

Would you still be justified in terminating its lineage? In denying it the life it so desperately seeks? Would you be righteous in overriding its desires and snuffing out the lights for good?

A creature so constructed would be one that clearly values consciousness over cursedness and anima over agony. It is a creature that would gladly trade another day of suffering in exchange for one last sunset.

Who are you to tell it otherwise?

This is my greatest objection to anti-natalism. Beyond the absurdity, beyond the pessimism, beyond the cowardice—it is the hubris that disturbs me most. The belief that because you have judged another creature’s life to be unworthy that this somehow gives you the right to extinguish it.

Sure, some preferences can be overridden by a knowledgeable authority. A gambling addiction. A terrible ex. Being a Jets fan.

But the desire to live simply isn’t one of them.

My problem with anti-natalists is not that they don’t mean well in trying to grant suffering creatures the gift of extinction. My problem is that it’s simply not their gift to give.

I do not consider this a minor transgression. Think of the “liberation” wars in the Middle East, or the communist revolutions, or the forced sterilization campaigns in India. All of them claimed to come with good intentions. All of them were trying to help. All of them were disastrous. And these were human interventions! We know what causes humans to suffer and flourish! We are much further removed from animals, let alone insects.23

What belies all of these decisions, all of these horrific and disastrous mistakes, is an unshakeable, all-encompassing arrogance. The belief that some group is capable of moral patienthood but not moral agency—that it is therefore your job to choose what is best for them.

There are times when this is appropriate and necessary, children being the most notable example. But parents at least have been children themselves once, and the responsibility that parents have over their children is one which is demanded of them rather than sought by them.

It is entirely different to claim the mantle of representative—to put the fate of an entire species in your hands as their advocate and executioner. To justify such an act must require a level of certainty that our experiences cannot yield and which current science does not allow. It must require the eye of God. And so as a question of practical justification, the extinction of a foreign species for its own benefit is simply untenable.

I’m not saying that all animal welfare advocacy is bad. I’m not saying that you shouldn’t seek to make the world a better place. I’m not saying that trying to reduce suffering is not noble or good, nor am I saying that you may never advocate or speak on behalf of others.

Of course, you may.

You may speak for yourself.

You may speak for those over whom you bear direct responsibility.

You may speak for your family, for your country, or for your kin.

You may speak for the victims of horrors you yourself have suffered from and you may speak for the beneficiaries of gifts you yourself have received.

And if the circumstances are dire, and your certainty assured, perhaps you may yet speak for those who beg and plead for death.

But you do not speak for the bees.

Many readers objected to this premise in particular, and I originally had a whole section devoted to it, but frankly we just don’t have time. Suffice to say that yes, this 15% modifier is ridiculous if you interpret it as a measure of relative moral worth. However, note that it does not imply that seven bees are worth more than one human. Rather, it implies that one day of suffering for seven bees is worse than one day of suffering for one human.

Is that still absurd? Yes, but that’s only because Adelstein is non-speciesist. He is basing moral worth exclusively off of capacity for suffering and pleasure, and on that dimension alone, it’s not actually that weird to imagine that bee suffering would be 15% as intense as human suffering. Small creatures can still have intense qualia. Maybe you adjust that by a few orders of magnitude to 0.15% as intense, but his argument still largely goes through because there are just so many bees.

Personally, I’d probably let 1M+ bees suffer for a day before I’d let a human suffer for a similar time (and that’s being generous to the bees), even knowing that the actual pain felt by those bees might be equivalent to 150K humans. But that’s because I’m a speciesist bastard (and you probably are too). Nevertheless, this premise isn’t necessary for most of the arguments that I want to critique today so we shall be largely ignoring it.

So many, in fact, that this essay took 5x longer than I expected to because I had to trim down and ignore all of the petty objections that first-draft me could not help himself from making

Especially since many of my favorite writers on Substack are vegans and I don’t want to piss them off I respect their opinions and generally think they are well-reasoned

Hey! That’s the name of the show!

Or to use a less deontic normative primitive, we might say that eating honey is very bad.

Adelstein denies being a negative utilitarian, and in the strict sense, this is true. He does think that pleasure can outweigh suffering to justify positive-in-expectation lives, he simply thinks that insects do not achieve this. So while I do think he shares many instincts and dispositions with the negative utilitarians, I will focus this essay to his slightly less extreme form of anti-natalism.

Bentham’s Bulldog, from the comment section of “Don’t Eat Honey”

Bentham’s Bulldog, “Long-Run Human Impact On Wild Animal Suffering: Much More Than You Wanted To Know”

EDIT: This is particularly true for human anti-natalism, which Adelstein rejects. But that is a whole other can of worms and beyond the scope of this essay. Insect lives only today.

Notably, I do not care very much about the moral weight of honey bees, so long as it is non-zero. As mentioned in prior footnotes, the relative value of honey bees vs. humans is a topic that could be debated ad nauseum. But this relative value only matters if we are comparing the suffering of bees to something else that is valuable to humans (e.g., the tastiness of honey). I am uninterested in this calculation. Moreover, I am also not concerned about how the extinction of honey bees or other insects would affect human well-being. So for the sake of argument, let us assume that all of the honey bee genocide proposals are able to replace these bees with tiny nanobots that serve all necessary bee functions that generate utility for humans (and other animals) with no other noticeable costs. Would it be good to kill all of the bees in this scenario? That is the question I am interested in, and I take Adelstein’s answer to be yes.

Or at least the weighted average

This phrasing may seem like a bit of an exaggeration of Adelstein’s position, so allow me to clarify two points:

First, an anti-natalist could argue that there is a difference between avoiding actions which create more suffering lives vs. actively choosing actions which prevent suffering lives. This might allow one to endorse veganism but not omnicide. However, Adelstein, being a consequentialist, doesn’t really make this distinction, and regularly advocates for actions of the former kind (e.g., abstaining from honey) as well as the latter (e.g., increasing destruction of natural ecosystems to prevent reproduction).

Second, you might also wonder if life prevention is the only option here. But note that Adelstein is not calling for beekeeping reform. He is not arguing that we should improve the lives of bees; he is saying that we should eliminate them. Part of this issue is that he simply thinks improving their lives is pointless; that insects such as bees are likely incapable of having net positive lives. We’ll come back to this later. But for now, just understand that the only options on the table (in his mind) are a life of suffering or no life at all.

See the later discussion on the inherent value of living.

He says, before proceeding to nitpick the details.

Per ReThink Priorities upper 2017 estimates, 43B bees are transported per year. Assuming the average lifespan of a bee is 10 weeks (3-4 weeks in the summer, but up to 6 months in the winter, ignoring queens), then using their estimates of 2.7M colonies and 24,000 bees per colony, total bee turnover per year is: ~333B. 43 / 333 = 13%

I tend to agree with Trace’s take that this view is somewhat incoherent—the act of satisfying a desire is inherently positive valence. It might not mean much, but it’s something. But we can ignore this issue for now.

I am assuming that the bee’s brain essentially shuts down most pain receptors during this process. But I mean, even if it doesn’t…worth it?

Or whatever the number is. Again, the exact conversion rate isn’t important for this discussion

Perhaps Adelstein would say that our higher pleasures such as friendship, love, and learning are not higher valence, just higher value. But for that to make sense, we must still have some sense, awareness, or judgement via which we may observe those virtues to be more choiceworthy than mere hedonic pleasure. Why might bees not have something similar?

Some of you might object to my phraseology here. Perhaps you believe that a “negative valence experience” is one which, by definition, you would disprefer over not existing for that period of time. If you prefer that definition—which necessarily denies the existence of an independent value of life that is disconnected from our measure of valence—then what my argument is actually saying here is that most painful experiences are not actually negative valence, and that most non-painful experiences are actually incredibly positive valence in ways that go under-appreciated. Is pure, unfiltered, isolated pain a negative valence experience? Sure. But almost no experiences are actually like that, and instead there are countless little joys and impressions on our consciousness that make seemingly bad experiences actually net positive. You may very well deny this, but just know that I think you’re weird.

Note: I’m not saying here that all painful experiences are necessarily net positive by virtue of them being experienced by a lived being. Yes, I would rather not exist than slowly be tortured to death. Obviously. But most pains are not that severe, and in many instances, I would absolutely pick experiencing said pain over not existing for those moments. I do not want to be Severed.

This is especially true the fewer experiences that I am allowed to have. An old woman might choose not to tolerate another mediocre day on this earth because she has already had so many; a child with cancer not so much. I do not deny that life may have a declining marginal utility the more of it you have, just like any other good. But that means bees—which only live for three or four weeks—are subject to some of the highest marginal utility gains from their brief experiences on earth.

By the way, the above is part of what makes the repugnant conclusion so repugnant—because a life that is barely worth living is actually pretty awful. It involves a metric ton of pain and hardship and toil. Because even after all of that, we living beings would do anything to remain alive.

I know this is not actually Adelstein’s argument, and I mostly include it here for rhetorical effect, but I would be remiss if I failed to note that this position would, I think, be justified under the views of Brian Tomasik. This is because he holds an odd interpretation of personhood and justification where future time-slices of the same being are different “persons” from that being today, and so even a life which is net positive involves making one “person” happy at another “person’s” expense, which Tomasik holds to be wrong.

Moreover, not only is animal anti-natalism less justified due to the lack of proximity with the victims, it is also, in a way, more dangerous. At least when death is a necessary evil, as in war or revolution, its cost must be weighed against the subsequent goods being sought. There is, in theory, a limit.

But when death is the good? There is no telling what havoc may be wrought. We must tread this ground with exceeding caution. I hate to imagine what a high-agency anti-natalist would do.

Great post! I definitely agree there's a lot of hubris, and not nearly enough intellectual curiosity, underlying a lot of these takes on wild animal suffering. In some sense, it's a weird mirror image of the pro-life movement, in that both are built around this totally silent and morally pure class of victims you can project your own views onto without any need to consider what their own perspective would be. I get why utilitarians are drawn to things like this, since insects and other "lower" animals are easy to conceptualize as pure "utility containers" in a way that avoids a lot of the complications we run into when we look at social issues involving human beings. But that sort of incurious paternalism is dangerous everywhere, I think.

(haven't finished reading yet, but):

> But while anti-natalism doesn’t fail on theoretical grounds, we can show that it fails as a _practical matter_: that as **limited** beings in **this** universe, we are **not justified** in **concluding** and **acting** upon the belief that large swaths of animal species are better off extinct.

This is beautiful. It feels like it rescues the whole thing by making a clear separation between (1) our ability to decide on the ethical option, given all known variables, and for all of us to agree on this, and (2) to reach a completely different conclusion given that we are not God, we do not have perfect information. Some information is in fact impenetrable, necessarily unknown given the range of our senses & actions, and the specific vantage point we take as actors of a certain species inside this world.

Now the correct choice in (2) is very different, BUT we don't make the mistake of letting go of (1), the platonic view of perfection that is our guide that we try to pull our world towards.